Fright Night

Twitter giveth and Twitter taketh away. For example, it dares us to spend some of our time replying to silly tweets such as "What are the three scariest words in your profession?" or something to that effect. Questions likes this taketh away our time, but giveth us an opportunity to learn in return.

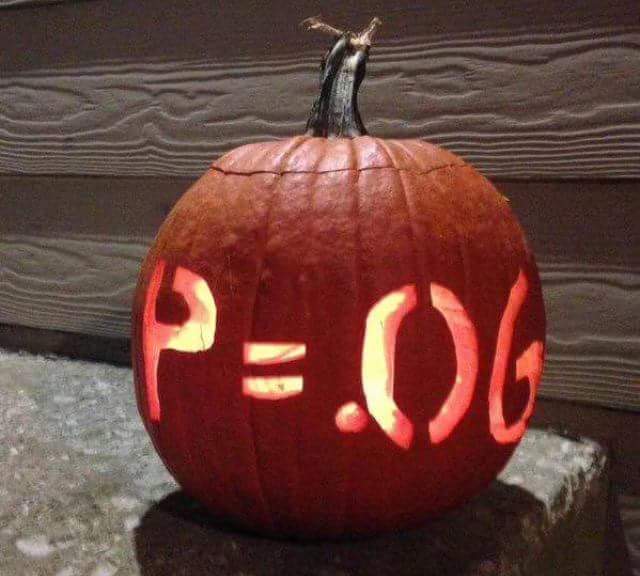

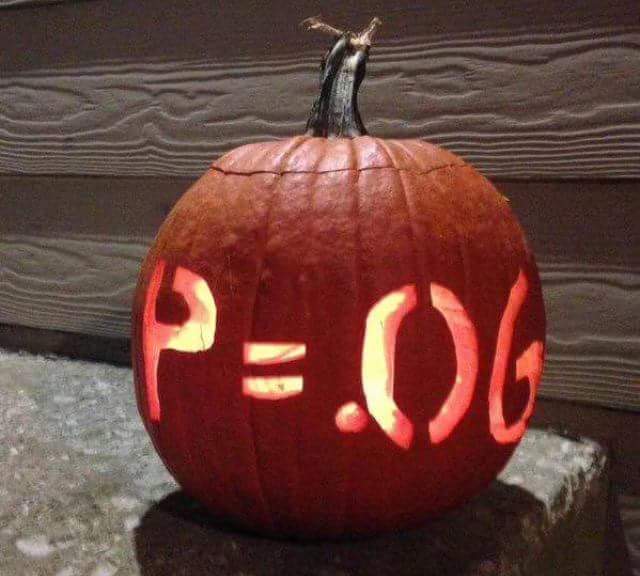

The opportunity to learn arises because when questions of the flavor of the one above arise, empirical researchers are often quick to respond something akin to ...

Romer, D. (2020), "In Praise of Confidence Intervals," AEA Papers and Proceedings, 110, 55-60

Many researchers laugh at such responses, but then secretly fear that this frightening creature is out there, lurking, ready to pounce on their own brilliantly conceived research plan.

Clearly, this is in good fun. Except when it's not. Behind every joke is an element of truth. And so these jokes really bother me. At risk of being a downer, such jokes help statistically significant results (i.e., instances where the null hypothesis that a parameter is equal to zero are rejected) maintain their place atop a pedestal in our culture of empirical research.

Why are significant results so highly coveted? Abadie (2020, p. 193) states:

"Nonsignificant empirical results ... are notoriously hard to publish in professional / scientific journals ... in part maintained by the widespread notion that nonsignificant results are non-informative."

However, as Abadie (2020) demonstrates in considerable detail, equating statistical significance with informativeness is just plain wrong. Instead, the informativeness of a study about an unknown parameter is inversely proportional to the size of the set of values for which we cannot reject the null hypothesis. In other words, the more of the parameter space we can eliminate, the more informative our study is. If this seems obvious, it's because it should be.

Fortunately, this is exactly the information conveyed by a confidence interval. A confidence interval tells us all the values in the parameter space for which we fail to reject the null that the parameter is equal to that value for a given significance level. Thus, a study is informative if the confidence interval is sufficiently narrow. Notice, nowhere in this definition of informativeness do I mention which values are included in the confidence interval; only the size of the interval itself.

Support for this notion can be found in Romer (2020), where he advocates for greater presentation and discussion of confidence intervals. Focusing on confidence intervals allows researchers and readers to distinguish between precisely estimated zero values of parameters and imprecisely estimated values that preclude the exclusion of zero. This distinction is written beautifully in Baicker & Chandra (2017, p. 2414):

"There is also a key difference between 'no evidence of effect' and 'evidence of no effect.' The first is consistent with wide confidence intervals that include zero as well as some meaningful effects,

whereas the latter refers to a precisely estimated zero that can rule out effects of meaningful magnitude."

The bottom line is that a precisely estimated zero is informative and, hence, should not be described as the stuff of nightmares.

Any Bayesians reading this are probably feeling left out by my focus on the merits of confidence intervals. Of course, in the Bayesian paradigm posterior credible intervals convey similar information about the informativeness of the data combined with the prior about a parameter of interest.

Where was I before the Bayesians interrupted me? Ah, yes ... The conflation of statistical significance and informativeness also leads to a related problem that seems far too prevalent if Twitter reflects real life: equating statistical significance with scientific interest. This seems to be part of a broader problem in science -- at least according to Twitter -- whereby papers are often rejected by reviewers due to "unsurprising" results.

The general point that we all need to be better about is the following. A paper should be deemed interesting if the research question is interesting, the research question has not been adequately answered in the existing literature, and the empirical analysis provides a reasonable answer to the question.

Notice, nowhere in this definition of interesting do I mention what the answer actually is. If the question is ex ante interesting and the analysis is reasonable, then an informative study should not become ex post uninteresting because of the answer. If the answer is a (precise) zero, then we have answered an interesting question. If the answer is a (precise) non-zero, but small (in absolute value) number, then we have answered an interesting question. And, if the answer is a (precise) non-zero, but large (in absolute value) number, then we have answered an interesting question. A particular answer may make the study more interesting, but it cannot and should not make it any less interesting.

When we deviate from this by conflating statistical (and economic) significance with interesting, then we end up with at best a replication crisis and at worst a replication crisis borne from questionable research practices. That's truly frightening, as is discouraging researchers from answering important questions that may lead to null findings.

Abadie (2020, p. 206) concludes:

"Our results challenge the usual practice of conferring point null rejections a higher level of scientific significance than non-rejections. In consequence, we advocate visible reporting and discussion of nonsignificant results in empirical practice... More generally, ... the weight of statistical evidence should not be primarily assessed on the basis of statistical significance. Other factors, such as the magnitude and precision of the estimates, the plausibility and novelty of the results, and the quality of the data and research design, should be carefully evaluated alongside discussions of statistical significance or of the magnitude of p -values."

References

Abadie, A. (2020), "Statistical Nonsignificance in Empirical Economics," American Economic Review: Insights, 2, 193-208

Baicker, K. and A. Chandra (2017), "Evidence-Based Health Policy," New England Journal of Medicine, 377, 2413-2415

Romer, D. (2020), "In Praise of Confidence Intervals," AEA Papers and Proceedings, 110, 55-60